In our area of work, my fellow researchers and I are exploring a set of research questions inspired by our ongoing assessment of the pressing issues for sustainable value creation arising from public investment in cultural institutions. While these issues are of relevance across the breadth of the arts and creative sectors, in this blog post I wish to draw particular attention to public service broadcasters (further posts will follow, looking at issues in the Arts and Culture portion of our remit). In order to highlight several pertinent matters at stake, it is necessary to step back and offer a brief sketch of the wider debates within which relevant policymaking has found its shape and direction over the years.

Not surprisingly, precisely what counts as ‘public service broadcasting’ varies from one national media system to the next around the globe. Common to most definitions, however, is the understanding that it revolves around a public service ethos, one that may be compared and contrasted with the economic (profit-oriented) priorities of private or commercial broadcasting. That is to say, the term is typically employed to describe those systems which strive to advance certain civic aims and normative values as a means to redress perceived market shortcomings.

Here we begin by recognising a continuum of sorts exists between the minimalist model of public service broadcasting introduced in the United States, on one end, and that developed in countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan and Australia, on the other. In the US, this type of programming constitutes a small proportion of audience share in television and radio, and is perceived to be of marginal significance in public life. The reverse is the case in the UK, where public service broadcasting – led by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) – continues to be the predominant institutional arrangement wielding considerable influence. Public broadcasting systems around the world can be situated within the parameters of this continuum.

From its origins in the 1920s, the BBC has pioneered a conception of public service broadcasting that is free of commercial advertising and, in theory, political influence. Its mission statement, as expressed by John Reith, the Corporation’s first Director-General, is to ‘inform, educate and entertain’. Funded primarily through a licence fee system, the BBC is currently the largest public broadcaster in the world. Its annual budget (about £3.7 billion in 2018) enables it to offer a comprehensive provision of programming – news, current affairs, arts and entertainment – across radio, television and the internet to reflect the diverse lives of our national, regional and local communities. Facing intensifying pressures from commercial rivals (both nationally, primarily from ITV and Sky, as well as globally, with new entrants such as Amazon and Netflix), it strives to balance its public service remit with a commitment to attracting wide audiences to its services. In addressing these audiences as citizens, as opposed to prospective consumers, the BBC’s preferred definition of the public interest should, in principle, prevail over and above what may interest the public at a given moment.

Since its inception, the evolving BBC model has proven to be considerably influential, with several of its main tenets closely emulated in a variety of national contexts. The social and moral ideals of the Reithian conception of public service, thrown into sharp relief by profit-led alternatives, have informed broadcasting’s development throughout the Commonwealth from the 1930s onward (examples include the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation). The BBC model similarly served as an exemplar for several countries in Europe, Scandinavia and Asia, as well as some previously aligned within the former Soviet Union. Many commentators in the early days believed the capacity of broadcast news and current affairs programming to shape ‘the public agenda’ signified the electronic media were providing a progressive, even democratising function with regard to public enlightenment about social issues and problems. Other commentators were far more pessimistic, arguing that the lack of direct democratic accountability over broadcasting institutions was ensuring public service would always be rendered subordinate to their financial performance.

As will be apparent from this discussion so far, several of the most contentious issues – and conflicting philosophies – informing the historical evolution of public service broadcasting remain pertinent to us today. It is recurrently the case that national systems have evolved to the point where they have come to rely, to varying degrees, on commercial revenue to meet operating costs. This trend appears to be accelerating, with powerful business interests often acting in concert with ‘market-friendly’ regulatory authorities (their strictures perceived to lack sufficient bite to be meaningful). In the case of network newscasts, for example, critics point to numerous examples where public broadcasters strive to avoid controversy for fear of offending either advertisers or government officials. Such apprehensions routinely lead to self-censorship, thereby calling into question the networks’ provision of impartial journalism consistent with public expectations of a reasonably balanced and fair presentation of opposing viewpoints on particular issues.

Most evaluative appraisals concur the future for public service broadcasting is far from assured. For some critics, its privatization is seriously overdue. They have long maintained that government involvement in broadcasting is an inappropriate use of taxpayers’ monies and, moreover, poses a threat to freedom of expression that only a market-based system can adequately preserve. Some claim to detect a ‘liberal bias’ in its programming, which they insist is out of step with popular opinion (allegations over ‘biased reporting’ on global warming, immigration or trade agreements being obvious examples of polarisation). Still others contend that evidence of declining audience figures for public service broadcasting in some countries constitutes evidence that commercial television more than satisfies public demand, particularly when set in relation to the growing salience of for-profit cable, satellite and web-based alternatives.

Advocates of public service broadcasting, in sharp contrast, highlight what they perceive to be the deficiencies of ratings-driven commercial media. Many of them believe it caters to a wider spectrum of interests than those which advertisers are inclined to support, thereby addressing important gaps in programming – news and documentary being regularly cited in this regard, as well as children’s content or regional voices and perspectives. While conceding that overall audience figures may be in decline in some national contexts, they nevertheless point out that a high percentage of viewers and listeners are decision-makers in business, political, scientific, cultural and educational realms whose perceptions of programme quality contrast with the ‘lowest common denominator’ orientation of some commercial networks. Hence the calls made for new types of support to be introduced so as to offset both political pressures and the influence of corporate financing, and thereby better reflect the values, tastes and preferences of diverse interest communities.

New challenges are emerging for public service broadcasting across its varied inflections in different national contexts. The era of interactive, high-definition digital technologies and mobile devices, together with new video-on-demand players and streaming services, poses important questions about its continued viability. The growing competition for viewers, together with contending claims on governmental support, raises concerns about how best to maintain a public service ethos for a type of broadcasting increasingly being fragmented into narrowcasting. While some insist that public service broadcasting is no longer relevant or necessary in a multi-channel universe, others believe that its daily reaffirmation of common civic values in a time of ‘fake news’ and ‘filter bubbles’ underscores a vital contribution it makes to enhancing mutual understanding and dialogue in public life.

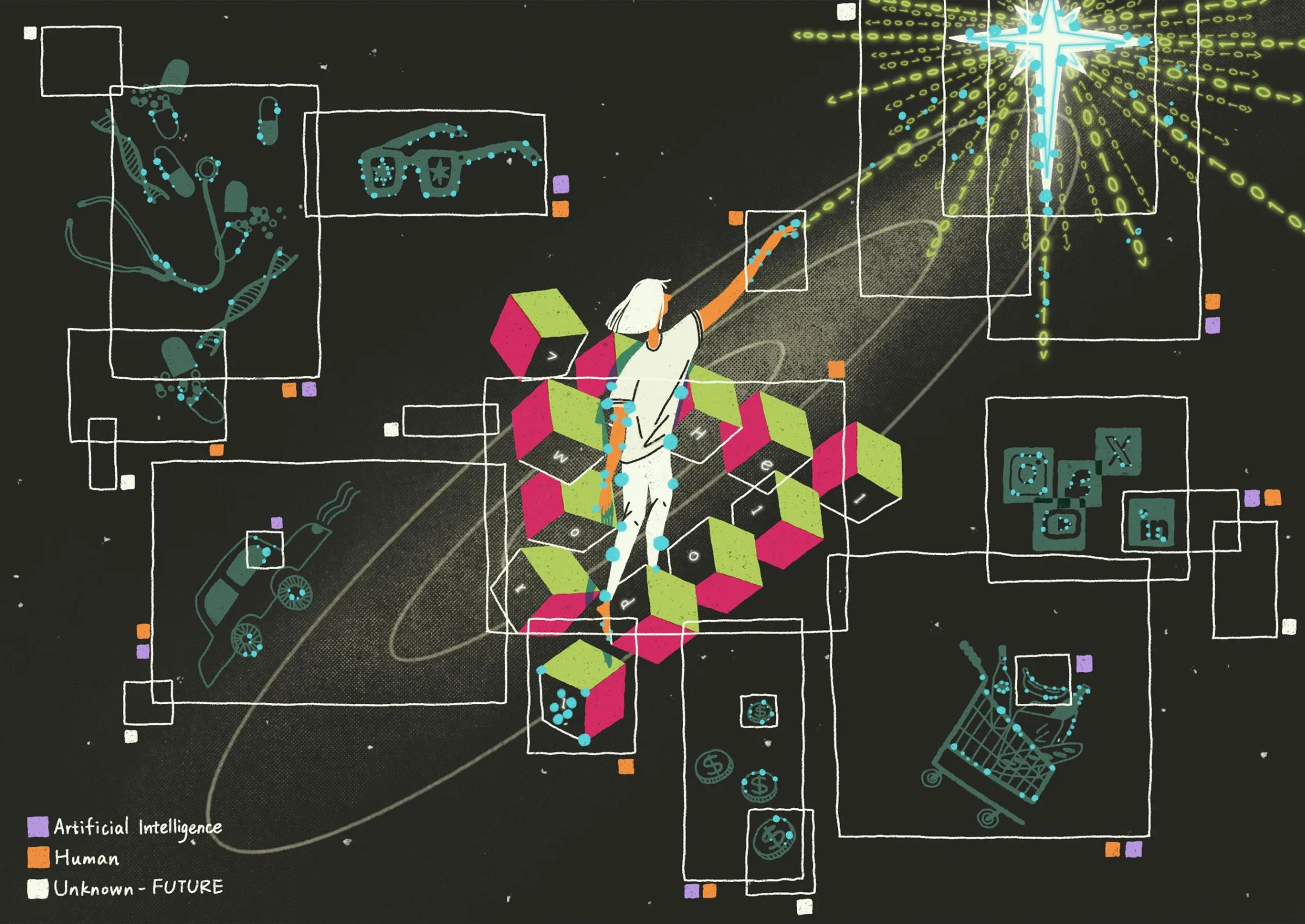

My aim in this blog post has been to briefly introduce and contextualise several of the issues at stake in this area of work’s first phase of operation as we strive to better understand the opportunities and risks for sustainable public value creation in the creative industries arising from public investment. Of particular interest for policymaking, our research thus far suggests, are key debates currently revolving around funding models and regulation, collaborative synergies across platform expansion, innovation in digital technologies (including experimentation in data analytics and personalisation), and audience engagement within new media ecologies. In a period of considerable uncertainty for cultural institutions and broadcasters, our area of work asks how best to recalibrate public investment to support the creation of value, and ensure their economic viability and cultural distinctiveness across the UK.

Please consider this blog post to be an invitation to you to get in touch with your thoughts, suggestions and concerns. We hope to establish a forum for everyone interested in participating, and are already planning further posts to follow in the weeks ahead. Welcome to the discussion!

Suggested reading

Abbott, S. (2016). Rethinking Public Service Broadcasting’s Place in International Media Development. Centre for International Media Assistance. Available at: https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CIMA_2016_Public_Service_Broadcasting.pdf [Accessed March 2019]

Bennett, J., Kerr, P., Medrado, M. and Strange, N. (2012). Multiplatforming Public Service Broadcasting: The economic and cultural role of UK Digital and TV Independents. London Metropolitan University, Royal Holloway, University of London, University of Sussex. Available at: http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/21021/1/bennett-strange-kerr-medrado-2012-multiplatforming-psb-industry-report.pdf [Accessed March 2019]

BBC, (2018). BBC Annual Plan 2018/2019. Available at: http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/aboutthebbc/insidethebbc/howwework/reports/pdf/bbc_annual_plan_2018.pdf [Accessed March 2019]

Donders, K., Lowe, G.F., Van den Bulck, H. (2018). Public Service Media in the Networked Society. Gothenburg, Sweden: Nordicom.

European Broadcasting Union, (2012). Empowering society: A declaration on the core values of public service media. Available at: https://www.ebu.ch/files/live/sites/ebu/files/Publications/EBU-Empowering-Society_EN.pdf [Accessed March 2019]

Freedman, D. (2016). A Future for Public Service Television: Content and Platforms in a Digital World. Goldsmiths, University of London. Available at: http://futureoftv.org.uk/report/ [Accessed March 2019]

Grant, A and Wilson, G. (2017). #NotWithoutMe A Digital World For All? Carnegie UK Trust. Available at: https://d1ssu070pg2v9i.cloudfront.net/pex/carnegie_uk_trust/2017/10/NotWithoutMe-2.pdf [Accessed March 2019]

House of Lords Select Committee on Communications, (2016). BBC Charter Review: Reith not revolution. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201516/ldselect/ldcomuni/96/96.pdf [Accessed March 2019]

Lowe, G.F. and Martin, F. (2013). The Value of Public Service Media. Nordicom. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.738.9565&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Accessed March 2019]

McElroy, R., and Noonan, C. (2018). Public Service Media & Digital Innovation: The Small Nation Experience. Public Service Media in the Networked Society, [online], p.159-174. Available at: https://www.nordicom.gu.se/sites/default/files/kapitel-pdf/10_mcelroy_noonan.pdf [Accessed March 2019]

Ofcom, (2017). Public service broadcasting in the digital age. Available at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/111896/Public-service-broadcasting-in-the-digital-age.pdf [Accessed March 2019]

Related Blogs

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.

When Data Hurts: What the Arts Can Learn from the BLS Firing

Douglas Noonan and Joanna Woronkowicz discuss the dangers of dismissing or discarding data that does…

Rewriting the Logic: Designing Responsible AI for the Creative Sector

As AI reshapes how culture is made and shared, Ve Dewey asks: Who gets to create? Whose voices are e…

Reflections from Creative Industries 2025: The Road to Sustainability

How can the creative industries drive meaningful environmental sustainability?