The UK Government’s ‘Levelling Up’ agenda aims to address regional disparities in economic prosperity and the impact these differences have on “people’s lives through their pay, work opportunities, health and life chances”.

The prospectus for the Levelling Up Fund explicitly acknowledges the role cultural infrastructure can play in rejuvenating places, leading to “positive economic and social outcomes at a local level”. Alongside the Treasury’s review of the ‘Green Book’ and the evolving Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital framework from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), the dial seems to be shifting towards a more holistic understanding of the impact that cultural investment might have in the realisation of macro-level policies. But without a direct role in the development or distribution of ‘Levelling Up’ funds, the DCMS will need to make the case for the cultural sector across multiple Whitehall departments.

Evidence emerging from the UKRI funded ‘Impact of Covid-19 on the cultural sector’ project, led by the Centre for Cultural Value in collaboration with the PEC and Audience Agency, tells us that pre-existing socio-economic inequalities that are closely associated with geography are being compounded by the disproportionate impact the pandemic is having on younger freelancers, disabled people, women, and people from black and ethnic minority backgrounds. Without access to private insurance schemes, a lag in consumer confidence and the gradual winding down of the furlough scheme, the true scale of the pandemic’s impact on the cultural sector is yet to be felt. Furthermore, there is evidence of an increased emphasis on localised participation, meaning that investment in local cultural infrastructure has never been more important.

Indeed, we have also written about how partnerships between local government and the cultural sector in Greater Manchester have allowed for a placed-based response to the pandemic.

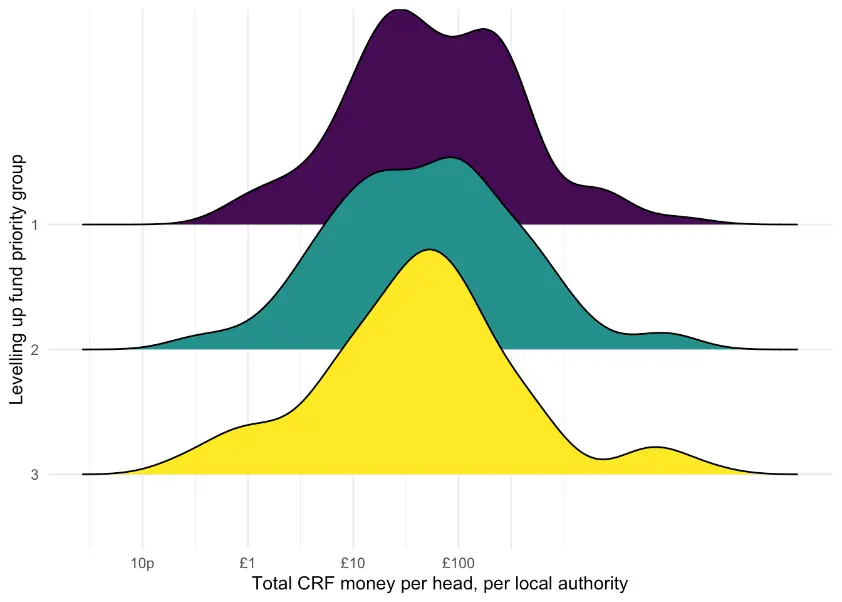

Analysis of the allocation of Rounds One and Two of the Cultural Recovery Fund (CRF) distributed by Arts Council England, National Heritage Lottery Fund and BFI shows that when it comes to accessing emergency funds, place matters. Figure 1 shows there are similar patterns of distribution of CRF per capita across all three tiers of the Government’s ‘Levelling Up’ priority areas (banded by measures of productivity, unemployment rates, transport connectivity and regeneration).

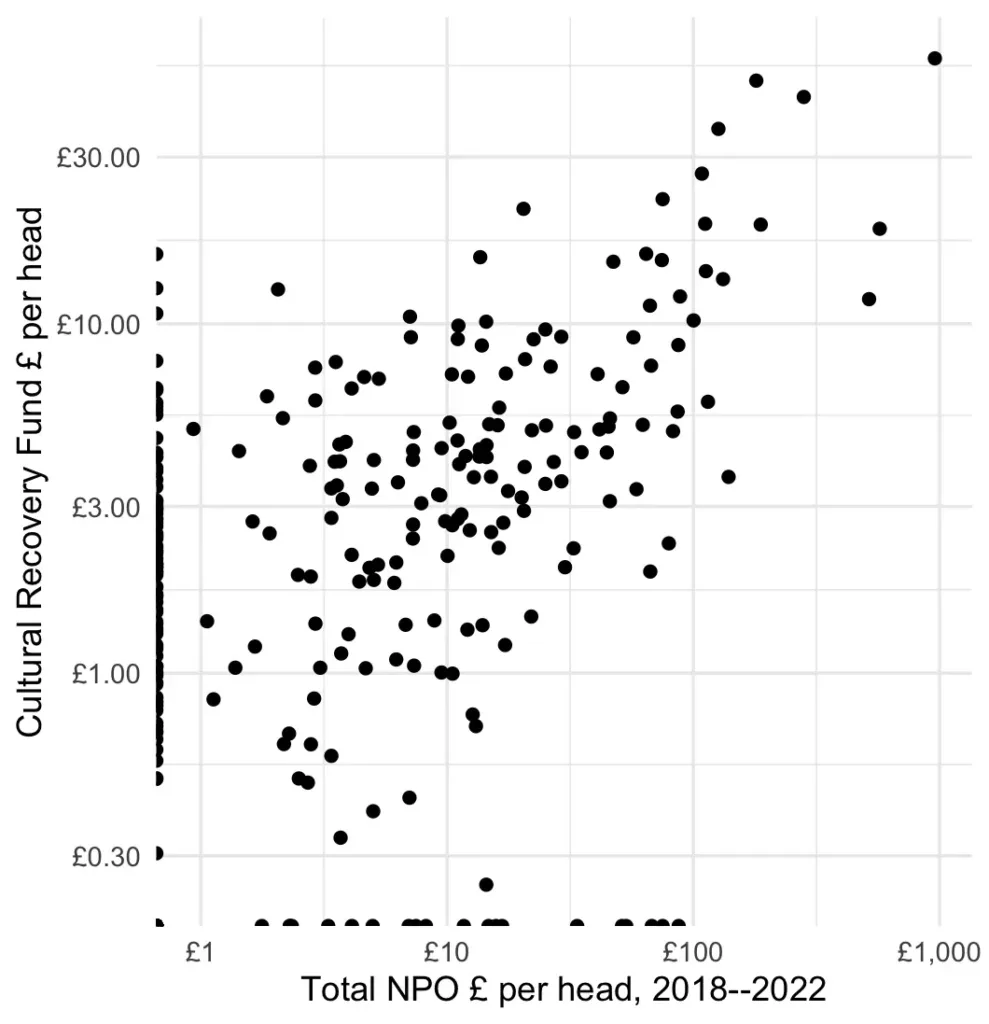

But a closer analysis reveals that those areas with lower levels of deprivation, existing flagship cultural institutions and larger numbers of National Portfolio Organisations (NPOs) were more likely to receive more CRF investment per head, perpetuating the maxim that ‘existing funding attracts future funding’. Figure 2 shows that when plotted against NPO funding, Arts Council England CRF grants have largely followed patterns of where culture funding has gone before.

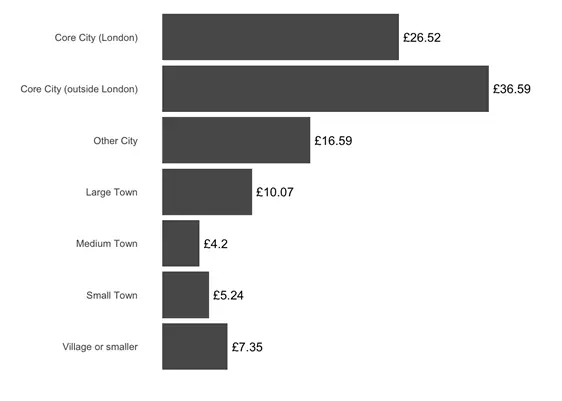

When plotted against types of place, the per capita differences are even starker (see Figure 3). Whilst these findings suggest strong cultural institutions and creative clusters are important factors attracting emergency funding, they also point to the potential reproduction of structural, place-based inequalities that have been entrenched by the longer-term impacts of austerity.

- The case study of Greater Manchester offers a valuable insight into the contribution that ‘soft power’ might play in decisions around the distribution of future ‘Levelling Up’ funds. The Core city of Manchester and the wider city-region have placed long-term investment in the value of the cultural sector to broader social and economic policy objectives, evidenced in the integration of the creative industries as a growth sector in the 2019 Local Industrial Strategy and the publication of the region-wide Cultural Strategy in the same year.

Local governance combined with well-established culture teams, sector leadership and ebullient political buy-in enabled the combined authority to leverage existing relationships and networks to present a unified voice for the cultural sector at the most destabilising and uncertain moments of the pandemic. This capacity to lobby, champion and collaborate resulted in Manchester Central receiving the highest amount of CRF funding of any parliamentary constituency in the country at £44,659,226. Higher even than the cities of London and Westminster and almost double the next non-London based constituency of Bristol West (another Core city). The extent of this investment is largely due to the concentration of existing NPOs, but also comprises £21m of Cultural Capital Kickstarter funding for the Factory – the home of Manchester International Festival and a new Kickstarter training academy for creative skills for the city-region.

The legacy of partnership working across Greater Manchester has provided the infrastructure through which emergency investment to organisations has been able to be recirculated to the wider cultural ecology to some extent. Collaborative ventures such as the sector-led freelancer network GM Artist Hub and crowd-funded projects such as United We Stream are good examples of initiatives that bring together individuals and organisations from the publicly funded sector and creative industries across the conurbation.

However, recent Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre research suggests that agglomeration-based models based on cultural flagships affect places in a variety of ways, not all of them beneficial, and that capturing how spillovers “trickle out” to the wider economy is complex and requires further consideration by policy makers. Greater Manchester’s success in coordinating support for flagship institutions based in Manchester City Centre must not come at the expense of neighbourhood level activity across the conurbation. As one interviewee in the study noted:

A lot of the government support – a lot of the national funding agencies – have supported those existing organisations. What they haven’t been able to support, and what’s been difficult to access, is money to support the voluntary, community-led, grassroots organisations. So, your community theatres, you know, your am-dram societies. Those types of organisation that are absolutely driven by the community.

These peripheral, everyday modes of cultural participation are the most easily and frequently accessed by the majority of the population. Access to neighbourhood resources, combined with well-funded institutional offers, can meet more fully the social, health and wellbeing needs of residents and address inequalities of health and social care, as discussed in the Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s recent Social Glue report.

To a large extent, Greater Manchester is an exceptional case. Culture has been recognised locally and nationally through the granting of funds, as an engine for recovery and an important component of city-regional infrastructure. When attention eventually turns from emergency measures to recovery, prioritising investment outside London and the south-east could go some way to addressing the persistent regional gaps in the productivity and public funding that many ‘left-behind’ places face. As the CRF opens for a third round, policy makers should consider how they can close the gaps between areas with considerable cultural capital, and those places without flagship anchor institutions, NPOs or highly networked clusters.

There is now growing consensus that if we are to do something for a place, it should also be of the place. Cultural investment models can no longer be based solely on agglomeration or competition to attract investment that may compound existing inequalities further. ‘Levelling Up’ policy must take the particular needs and existing capacities of different places into account if there is any hope of creating a level policy playing field that equitably addresses social need and increases the health and wealth of the nation.

This report is being published as part of the PEC’s campaign Creative Places, which is calling for the government to invest in our local creative industries via targeted funding to creative microclusters

Image of Manchester’s canalside, by Lukas Noehrer.

Related Blogs

From Wales to the World: Why International Cultural Policy Needs a Future Generations Lens

This guest blog is from Professor Sara Louise Pepper, a member of our Global Creative Economy Counci…

10 facts about Creative Industries growth potential

Discover ten key findings from the report 'High-Growth Potential Firms in the UK's Creative Industri…

Why London is investing in Creative Enterprise Zones

London Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan announces £2.2 million in new funding for Creative Enterprise Zones.

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.